INTRODUCTION OF HELICOPTER EMERGENCY MEDICAL SERVICES IN CROATIA: A PERSPECTIVE FROM THE RECEIVING HOSPITAL

Introduction

Helicopter Emergency Medical Services (HEMS) have become an integral part of modern emergency medicine, providing rapid transport and advanced care for critically ill or injured patients, particularly in regions where ground-based services face limitations. The ability of HEMS to reach remote or hard-to-access locations and deliver on-site advanced interventions has been well documented (1–3). Globally, HEMS have been associated with improved survival rates and better patient outcomes in trauma and other time-sensitive conditions (4,5). However, some studies have questioned the extent of these benefits, reporting no significant difference in mortality when compared to ground emergency medical services (GEMS) (6,7).

In Croatia, emergency medical services have evolved significantly since the 1960s, expanding from urban centers to rural and remote areas (8). The introduction of HEMS was primarily driven by the need to improve response times in challenging terrains, including numerous islands and mountainous regions. Prior to March 2024, HEMS operations were predominantly along the Croatian coast. Recognizing the need for rapid medical interventions inland, HEMS services were extended to the rest of Croatia, with Dubrava University Hospital serving as the primary receiving center for the Zagreb region due to its operational heliport and advanced medical capabilities covering a diverse area of more than 21,000 square kilometers (9,10).

The implementation of HEMS in the Zagreb region aims to address geographical and accessibility challenges, ensuring timely medical interventions for patients requiring urgent transport to tertiary care centers. This includes those with severe trauma, acute cardiac events, neurological emergencies, and other critical conditions where rapid response significantly impacts outcomes (11,12). This study aims to describe patient characteristics, management and outcomes from the receiving hospital’s perspective.

Methods

Study Design

A retrospective observational analysis was conducted based on hospital information system and medical records from Dubrava University Hospital, including the Prehospital Critical Patient Alert reports (Appendix 1). The study covered the period from April to September 2024, corresponding with the initial six months of HEMS operation in the Zagreb region.

In Croatia, the process of activating Helicopter Emergency Medical Services (HEMS) typically begins when an emergency situation is reported, either through dispatch or by a field doctor on the scene who deems helicopter transport necessary. The activation involves assessing the patient’s condition and deciding whether HEMS is the most appropriate solution. Upon arrival at the scene, the medical crew, consisting of a doctor, and a nurse, stabilizes the patient for transport. During the flight, the medical team maintains ongoing care. Dispatch, and when possible, the HEMS team, communicates with the receiving hospital, such as Dubrava University Hospital, through mobile phones or TETRA radios. They provide relevant patient data, which is recorded in the Prehospital Critical Patient Alert (PCPA) by the emergency department triage nurse. The triage nurse activates the opening of the helipad and notifies the appropriate medical teams. Upon landing of the helicopter, the GEMS team receives the patient, who is transferred from the helipad to the emergency department (ED), approximately 300 meters away. Once the patient reaches the hospital, a detailed handover is performed, where the HEMS team or the GEMS team transfers essential patient information to the hospital staff. The hospital then integrates the patient data into the hospital’s information system for continuity of care. The ED team performs an initial assessment and manages the patient accordingly. The patient may then undergo diagnostic procedures, receive necessary treatment, or be transferred to the appropriate department for further care. This streamlined process ensures quick, coordinated, and efficient care for critical patients.

Data Collection

Data were collected on all patients transported by HEMS to Dubrava University Hospital during the study period according to the hospital information system and medical records. Variables included patient demographics (age and gender), transport times from dispatch notification to hospital arrival, medical interventions performed upon arrival (such as surgeries, percutaneous coronary interventions, and thrombolysis), and patient disposition and mortality.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were utilized to summarize the data. Median values were calculated for continuous variables such as age and transport times due to their skewed distribution. Categorical data were presented as frequencies and percentages.

Results

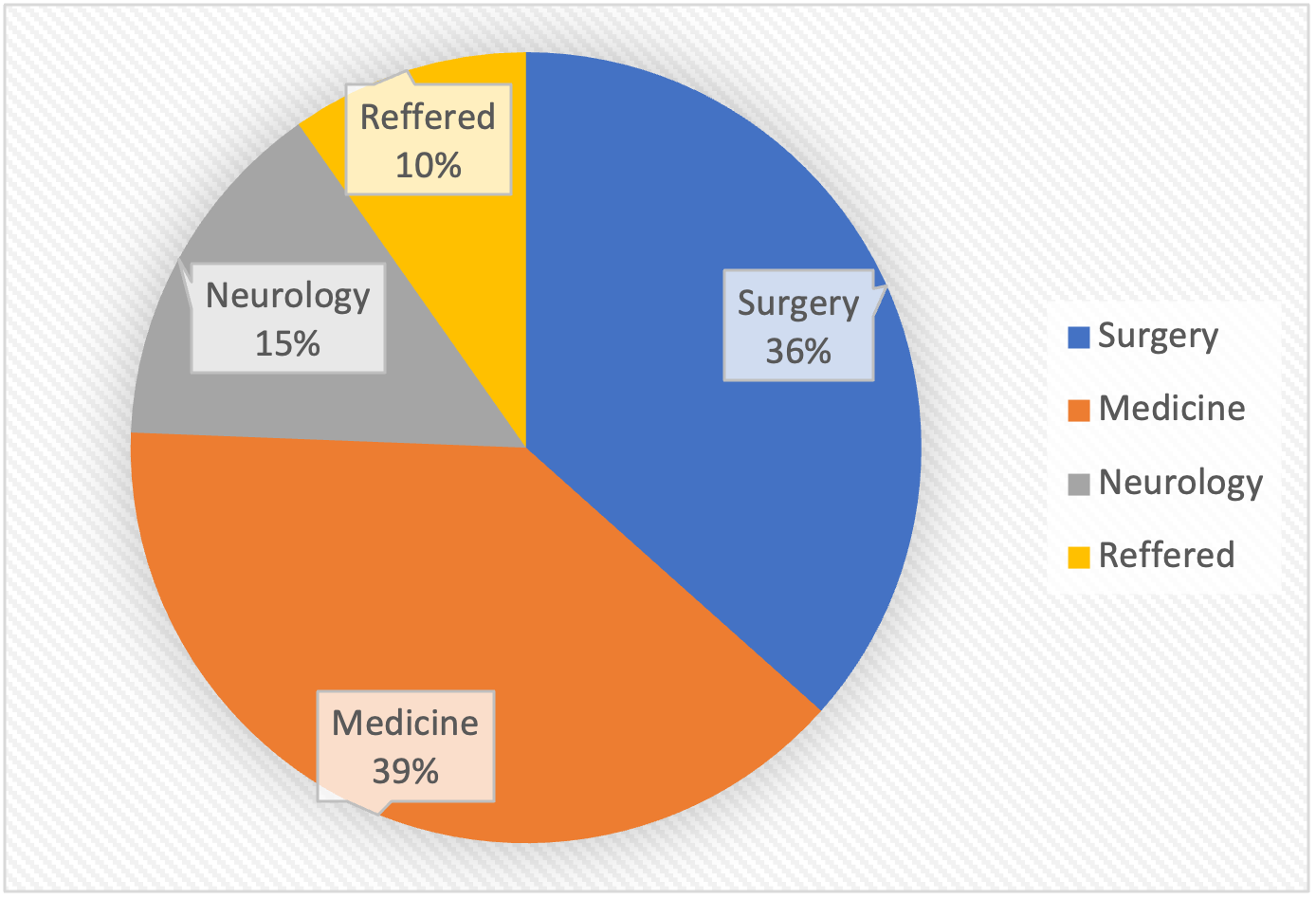

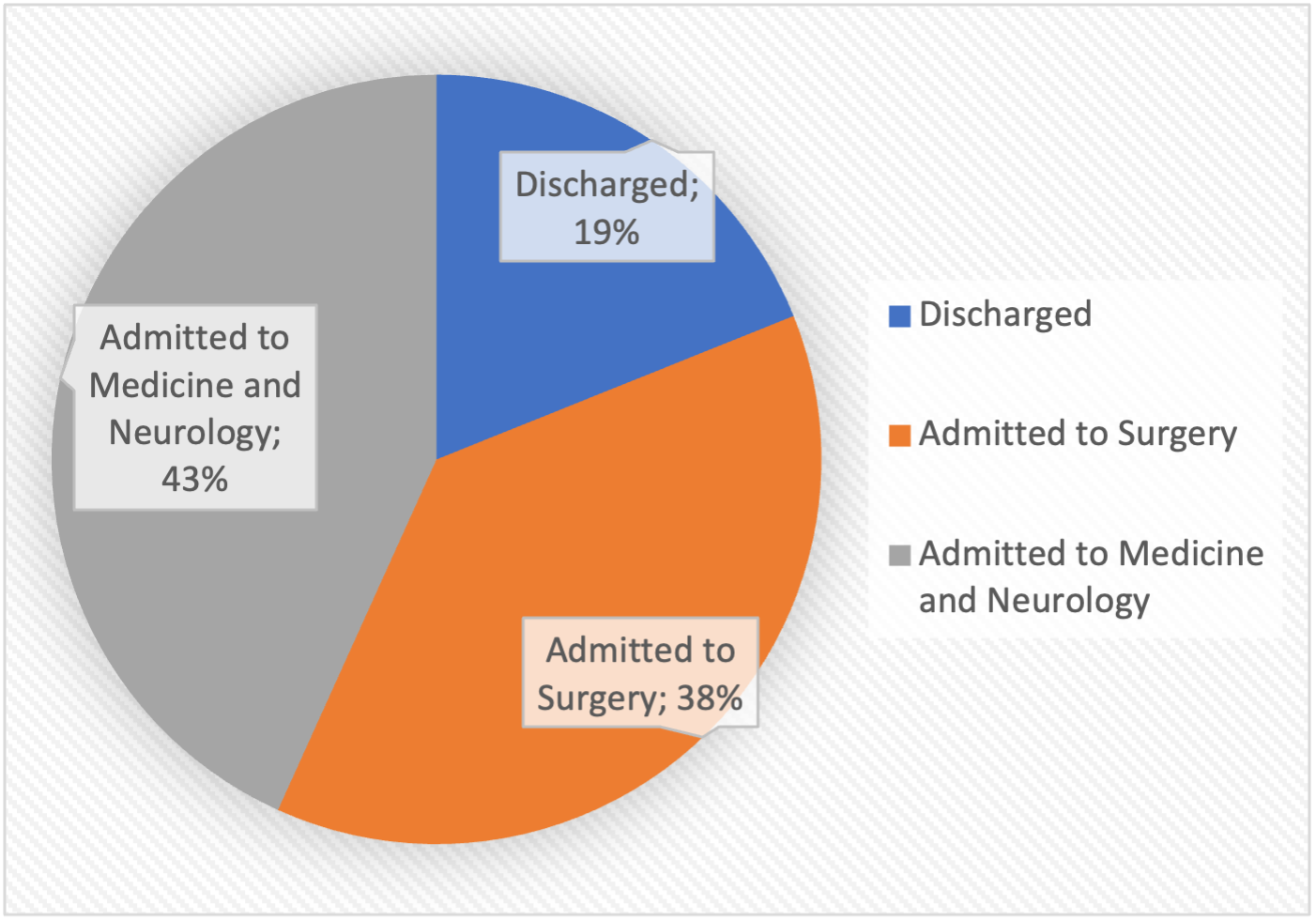

During the study period, we recorded 47 patients that were transported by HEMS to the Dubrava University Hospital. There were six PCPA reports with missing relevant data, meaning the intervention was cancelled or lost to follow up. The study included 41 patients in total, 29 (70%) male and 12 (30%) female patients. The age of the patients ranged from 18 to 80 years, with a median age of 63 years. The median transport time from dispatch notification to patient arrival at the hospital was 24 minutes, with transport times ranging between 7 and 59 minutes. The median Expected Time of Arriva (ETA) was 18.5 minutes with ETA ranging between 5 and 92 minutes. Advanced medical interventions were required in 20 patients (49%). These interventions included immediate surgery, percutaneous coronary interventions, and thrombolysis. Out of the 41 patients, 15 (36%) were treated surgically, 16 (39%) were treated and admitted to cardiology and internal medicine, 6 (15%) had neurological emergencies, and 4 (10%) were arranged in advance to be immediately transferred to other hospitals for definitive care, i.e. burns center, aortic aneurism center, etc. (Figure 1). Considering patient disposition, out of the 37 patients, 14 (38%) were admitted for surgical management, 16 patients (43%) were admitted for medical management, 7 (19%) were discharged on the same day after workup and observation in the ED (Figure 2). There were no recorded deaths in the ED, however two patients (5%) died during their hospital stay. In the PCPA reports, the most often reported information was the state of consciousness at 18 (44%) % and estimated time of arrival (ETA) at 32 (76%).

Discussion

The introduction of HEMS in the Zagreb region has substantially improved the capacity to deliver rapid medical care to critically ill or injured patients. The median transport time of 24 minutes underscores the efficiency of HEMS in overcoming geographical and logistical challenges that may delay GEMS. Rapid response is crucial for conditions where time to treatment is a critical determinant of outcomes, such as acute myocardial infarction, severe trauma, and acute stroke (11,12). The demographic distribution aligns with common patterns observed in emergency medical services, where a higher prevalence of critical conditions is often seen in older adults and males.

The introduction of HEMS in the Zagreb region enhances the rapid medical care of critically ill patients.

In our study, with a limited sample of interventions, the high proportion of patients requiring advanced medical interventions indicates that HEMS is effectively facilitating access to specialized care for patients in critical need. There was no lethal outcome reported in the emergency department and only 2 (5%) patients succumbed to injuries within 30 days of admission. While some studies have demonstrated survival benefits associated with HEMS, particularly in severely injured patients (13,14), other research has not found significant differences in mortality when comparing HEMS to GEMS (6,7). A Cochrane review by Galvagno et al. concluded that due to methodological weaknesses and heterogeneity among studies, it is unclear whether HEMS offers a significant advantage over GEMS in terms of mortality outcomes (6).

Our findings are consistent with international studies that highlight both the potential benefits and the complexities associated with HEMS. A Swedish study by Lapidus et al. reported lower mortality rates for trauma patients transported by HEMS despite longer prehospital times, suggesting that the advanced care provided by HEMS personnel offsets time differences (12). Conversely, a study by Beaumont et al. in England found a non-significant survival advantage for patients transported by HEMS and emphasized the challenges in statistically assessing HEMS benefits due to intrinsic patient demographic mismatches (7). Den Hartog et al. demonstrated a survival benefit with physician-staffed HEMS, showing an average of 5.33 additional lives saved per 100 dispatches among severely injured patients (13). However, the cost-effectiveness of HEMS remains a subject of debate. While some studies support the economic viability of HEMS (15), others highlight the need for careful resource allocation due to high operational costs (16).

Effective communication is critical in emergency medical services to ensure optimal patient care. Missing data in the PCPA reports suggests potential for improvement in communication exchange and streamlining patient care. Similar challenges have been reported in other regions, emphasizing the need for standardized communication protocols (17,18). Enhancing communication between HEMS teams, dispatch centers and receiving hospitals is essential to maximize the benefits of HEMS.

Another important observation is time from alerting the receiving hospital of the critically ill patient to the time of arrival. The activation of the hospital emergency response (surgical, medical, anesthesia, radiology, other specialists) for incoming critically ill patients transported via helicopter requires immediate reallocation of resources and personnel to prepare for the patient’s arrival. This process often involves staff interrupting ongoing tasks to ensure readiness and availability. However, when the estimated time of arrival (ETA) provided by the helicopter transport team or dispatch center is imprecise or significantly delayed, this creates a critical inefficiency. Prolonged waiting periods, sometimes exceeding 90 minutes, can lead to staff fatigue, distraction, and a decline in preparedness, as focus and team cohesion dissipate over time. Such disruptions not only waste valuable resources but may also negatively impact the team’s performance and readiness to provide optimal care upon the patient’s arrival (19-23).

Many factors contribute to the HEMS activation itself, which is not the topic of this paper. Nevertheless, there is always a potential for overutilization of HEMS resources for cases that may not have necessitated air transport. Overutilization of HEMS incurs unnecessary costs and diverts resources from patients who might benefit more significantly from rapid transport. A study from the Central Gulf Coast region in the United States found that 34% of HEMS transports were potentially unwarranted, resulting in unnecessary healthcare expenditures exceeding 3 million dollars (15). Considering that we are describing a HEMS program at the start of operations, the observation that 19% of patients were discharged on the same day can be considered part of the learning curve of the teams. According to international studies, activation criteria should focus on specific clinical indicators, severity scores, and geographical considerations (22,23). Standardized criteria can reduce inappropriate HEMS activations and allocate resources to patients who will benefit the most.

Advanced medical interventions were required in 20 patients (49%), including immediate surgery, percutaneous coronary interventions, and thrombolysis.

Implementing standardized communication procedures between HEMS teams, dispatch centers and receiving hospitals is critical. Dispatchers should provide comprehensive patient information, including vital signs, symptom duration, identification details, and estimated time of arrival. Utilizing technology to share real-time updates securely can further enhance coordination (16,17). Regular training programs for dispatch personnel and medical staff can improve assessment skills, adherence to activation criteria, and communication effectiveness. Training has been shown to enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of emergency medical services (17,25).

Establishing a centralized database to track HEMS interventions and outcomes can facilitate monitoring, evaluation, and continuous improvement. Data-driven approaches enable informed decision-making and policy development (8,26). Comprehensive data collection is essential for conducting cost-benefit analyses and assessing the long-term impact of HEMS.

Limitations

This study is based on observational data from a single center over a limited period. Findings may not be generalizable to other regions or healthcare systems due to differences in infrastructure and population demographics.

Collaborative efforts among policymakers, healthcare providers, and emergency services are crucial to optimize HEMS operations and deliver the best emergency healthcare.

Conclusion

The introduction of HEMS in the Zagreb region represents a significant advancement in Croatia’s emergency medical services, enhancing rapid medical care for critically ill patients. Initial observations indicate operational efficiency and effective facilitation of specialized care. There is room for improvement in communication between HEMS, GEMS and the receiving hospital. Future studies with more extensive data and comparative analyses are necessary to evaluate the long-term effectiveness and cost-efficiency of HEMS in Croatia. Collaborative efforts among policymakers, healthcare providers, and emergency services are crucial to optimize HEMS operations and deliver the best emergency healthcare.

References

- Galvagno SM Jr, Sikorski R, Hirshon JM, Floccare D, Stephens C, Beecher D et al. Helicopter emergency medical services for adults with major trauma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Dec 15;2015(12):CD009228. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009228.pub3..

- Brown JB, Gestring ML, Guyette FX, Rosengart MR, Stassen NA, Forsythe RM et al. Helicopter transport improves survival following injury in the absence of a time-saving advantage. Surgery. 2016 Mar;159(3):947-59. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2015.09.015

- Krüger AJ, Skogvoll E, Castrén M, Kurola J, Lossius HM. ScanDoc Phase 1a Study Group. Scandinavian pre-hospital physician-manned Emergency Medical Services–same concept across borders? Resuscitation. 2010 Apr;81(4):427-33. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2009.12.019.

- Den Hartog D, Romeo J, Ringburg AN, Verhofstad MHJ, van Lieshout EMM. Survival benefit of physician-staffed Helicopter Emergency Medical Services (HEMS) assistance for severely injured patients. Injury. 2015;46(7):1281-6. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2015.04.013.

- Apodaca A, Olson CM Jr, Bailey J, Butler F, Eastridge BJ, Kuncir E. Performance improvement evaluation of forward aeromedical evacuation platforms in Operation Enduring Freedom. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013 Aug;75(2 Suppl 2):S157-63. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318299da3e.

- Galvagno SM Jr, Thomas S, Stephens C, Haut ER, Hirshon JM, Floccare D, Pronovost P. Helicopter emergency medical services for adults with major trauma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Mar 28;(3):CD009228. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009228.pub2. Update in: Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Dec 15;(12):CD009228. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009228.pub3

- Beaumont O, Lecky F, Bouamra O, Surendra Kumar D, Coats T et al. Helicopter and ground emergency medical services transportation to hospital after major trauma in England: a comparative cohort study. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open. 2020 Jul 16;5(1):e000508. doi: 10.1136/tsaco-2020-000508.

- Croatian Institute of Emergency Medicine. Annual Report on Emergency Medical Services. 2022. [In Croatian].

- Croatian Helicopter Emergency Medical Service (HHMS). Operational Overview. 2023. Available at: https://hhms.hr.

- Hrvatska [Internet]. Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia; c2024 [cited 2024 Dec 30]. Available from: https://hr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hrvatska.

- De Luca G, Suryapranata H, Ottervanger JP, Antman EM. Time delay to treatment and mortality in primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction: Every minute of delay counts. Circulation. 2004;109(10):1223-5. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000121424.76486.20.

- Lapidus O, Rubenson Wahlin R, Bäckström D. Trauma patient transport to hospital using helicopter emergency medical services or road ambulance in Sweden: a comparison of survival and prehospital time intervals. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2023;31(1):6. doi: 10.1186/s13049-023-01168-9.

- Den Hartog D, Romeo J, Ringburg AN, Verhofstad MHJ, van Lieshout EMM. Survival benefit of physician-staffed Helicopter Emergency Medical Services (HEMS) assistance for severely injured patients. Injury. 2015;46(7):1281-6. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2015.04.013.

- Ringburg AN, van Lieshout EMM, Patka P, Schipper IB. Helicopter emergency medical services (HEMS): Impact on on-scene times. J Trauma. 2009;66(3):615-6. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000240449.23201.57.

- Ringburg AN, Polinder S, Meulman TJ, Steyerberg EW, van Lieshout EM, Patka P, van Beeck EF, Schipper IB. Cost-effectiveness and quality-of-life analysis of physician-staffed helicopter emergency medical services. Br J Surg. 2009 Nov;96(11):1365-70. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6720.

- Miles MVP, Beasley JR, Reed HE, Miles DT, Haiflich A, Beckett AR, Lee YL, Bowden SE, Panacek EA, Ding L, Brevard SB, Simmons JD, Butts CC. Overutilization of Helicopter Emergency Medical Services in Central Gulf Coast Region Results in Unnecessary Expenditure. J Surg Res. 2022 May;273:211-217. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2021.12.038.

- Ulvin OE, Skjærseth EÅ, Krüger AJ, Thorsen K, Nordseth T, Haugland H. Can video communication in the emergency medical communication centre improve dispatch precision? A before-after study in Norwegian helicopter emergency medical services. BMJ Open. 2023 Oct 29;13(10):e077395. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2023-077395.

- Sorani M, Tourani S, Khankeh HR, Panahi S. Prehospital Emergency Medical Services Challenges in Disaster; a Qualitative Study. Emerg (Tehran). 2018;6(1):e26.

- Rivera-Rodriguez AJ, Karsh BT. Interruptions and distractions in healthcare: review and reappraisal. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19(4):304-12. doi:10.1136/qshc.2009.033282.

- Johnson TM, Motavalli A, Gray MF. Causes and occurrences of interruptions during ED triage. J Emerg Med. 2013;45(2):150-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.08.045.

- Ratwani RM, Trafton JG, Boehm-Davis DA. Managing interruptions in healthcare: From theory to practice. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting. 2014;58(1):2065-9. doi: 10.1177/1541931214581148.

- Brixey JJ, Tang Z, Robinson DJ. Interruptions in a Level One Trauma Center: A Case Study. Int J Med Inform. 2007;76(9):620-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2006.09.012.

- Blocker RC, Heaton HA, Forsyth KL, Hawthorne HJ, El-Sherif N, Bellolio MF, Nestler DM, Hellmich TR, Pasupathy KS, Hallbeck MS. Physician, Interrupted: Workflow Interruptions and Patient Care in the Emergency Department. J Emerg Med. 2017 Dec;53(6):798-804. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2017.08.067.

- Association of Air Medical Services. Medical Transport Utilization Review Criteria. 2019.

- European HEMS and Air Rescue Committee (EHAC). Guidelines on Air Rescue Operations in Europe. 2018.

- Soreide, E., Grande, C.M. (Eds.). (2001). Prehospital Trauma Care (1st ed.). CRC Press. https://doi.org/10.1201/b14021.

Figure 1. Pie chart showing the distribution of patients by type of emergency

Figure 2. Pie chart presenting patient disposition

Published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License