Updating the 5 Es of Emergency Physician Performed Cardiac Point-of-Care Ultrasound: A Protocol for Rapid Identification of Effusion, Ejection, Equality, Exit, and Entrance

Introduction

Cardiac point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) has been performed in the Emergency Department (ED) for over 30 years and is among the most performed POCUS examination type both on its own and in combination with symptom-based protocols (1,2). A protocol described as the “5 Es” was proposed by our group in 2015 to help emergency physicians (EPs) assess for cardiac pathologies using POCUS (3). POCUS has continued to expand in both undergraduate medical education and residency training (3-6). The 5 Es are effusion, ejection, equality, exit, and entrance, and offer a way to standardize the performance and interpretation of cardiac POCUS.

While the 5 Es protocol offers a straightforward approach to cardiac POCUS, there has been additional evidence on the utility of cardiac POCUS published in the 10 years since the 5 Es protocol was first proposed. Advances in POCUS equipment, increased sonographer skills, and further research have helped to solidify the use of cardiac POCUS to make more accurate diagnoses of more conditions in the ED. Additionally, there is an increasing focus on artificial intelligence (AI) in cardiac POCUS, and these new tools help sonographers make accurate diagnoses with limited training (7-10).

This review aims to update the 5 Es and discuss further supporting research including any reinforcements or changes within the past 10 years, so that this approach can continue to serve as a tool for education and practice. Reading the original 5 Es manuscript prior to this review is recommended (3).

Effusion

Assessing for a pericardial effusion involves the operator using all cardiac views to look for a fluid collection in the pericardial space. A pericardial effusion can be graded from small (< 1 cm; 50-100 mL), moderate (1-2 cm; 100-500 mL), or large (> 2 cm; >500mL) (11). If a pericardial effusion is identified, the operator should evaluate for evidence of cardiac tamponade using the inferior vena cava (IVC) diameter and lack of collapsibility, mitral or tricuspid valve inflow velocity variation, visualization of right atrial (RA) systolic and/or right ventricle (RV) diastolic collapse, or hepatic venous flow patterns (11,12). Timely and accurate detection of a pericardial effusion is essential for expediting diagnosis and management, with POCUS having been shown to decrease the time to intervention (drainage) for patients with pericardial effusions (13). A recent study showed, however, that there is poor interrater reliability for some signs of cardiac tamponade. The lowest interrater reliability was found in parasternal short views and the highest in mitral valve inflow variation, suggesting that multiple images and clinical context should be used to diagnose cardiac tamponade (14). It is important to consider that conditions such as pulmonary hypertension may affect the pathophysiology of cardiac tamponade. A recent systematic review of 43 studies showed right-sided chamber collapse appears to be less likely to occur in the setting of increased intracardiac pressure and RV hypertrophy due to pulmonary hypertension (15). Among the results, it was found that the incidence of tamponade increased in patients with pulmonary hypertension. Additionally, only 10.5% of patients with pulmonary hypertension and tamponade showed right-sided chamber collapse, suggesting that the elevated right heart pressures withstood a higher pericardial pressure prior to collapse (15). Evaluation for the presence of pulmonary hypertension can be performed by looking for tricuspid regurgitation (TR) and measuring the pressure gradient using continuous wave Doppler, as discussed in the section on “E” for equality.

Artificial intelligence (AI) and the use of deep learning algorithms could help identify pericardial effusions, and eventually, signs of cardiac tamponade. While to our knowledge there are no commercially available products that detect pericardial effusion or signs of cardiac tamponade, there are publications showing the feasibility of detecting and quantifying pericardial effusion. Cheng et al. developed a machine-learning algorithm to automatically calculate the width of a pericardial effusion using ultrasound video clips (16). Additionally, a deep learning algorithm has been used to calculate mitral valve inflow velocities (17). As of this writing there is a preprint of a manuscript that reports reasonable accuracy in detecting moderate to large effusions and signs of tamponade (18). These novel AI applications demonstrate a proof of concept that in the future the diagnosis of cardiac tamponade could be automated.

Ejection

Assessing for overall left ventricular (LV) cardiac function or “ejection” can help provide immediate information in patients with chest pain, shortness of breath, hypotension, or syncope. Prior research has shown that emergency physicians are accurate in visually determining whether ejection fraction (EF) is preserved (EF > 50%), moderately reduced (EF 30-50%), or poor (EF < 30%) without needing to assess the EF quantitatively (19-21). POCUS operators can use this information to make a new diagnosis of congestive heart failure, expediting patient workup and care.

The last decade has seen significant improvements in POCUS technology, sonographer skills, and research, enhancing its ability to diagnose various cardiac conditions. Artificial intelligence (AI) is now playing a crucial role, helping less experienced users make accurate diagnoses.

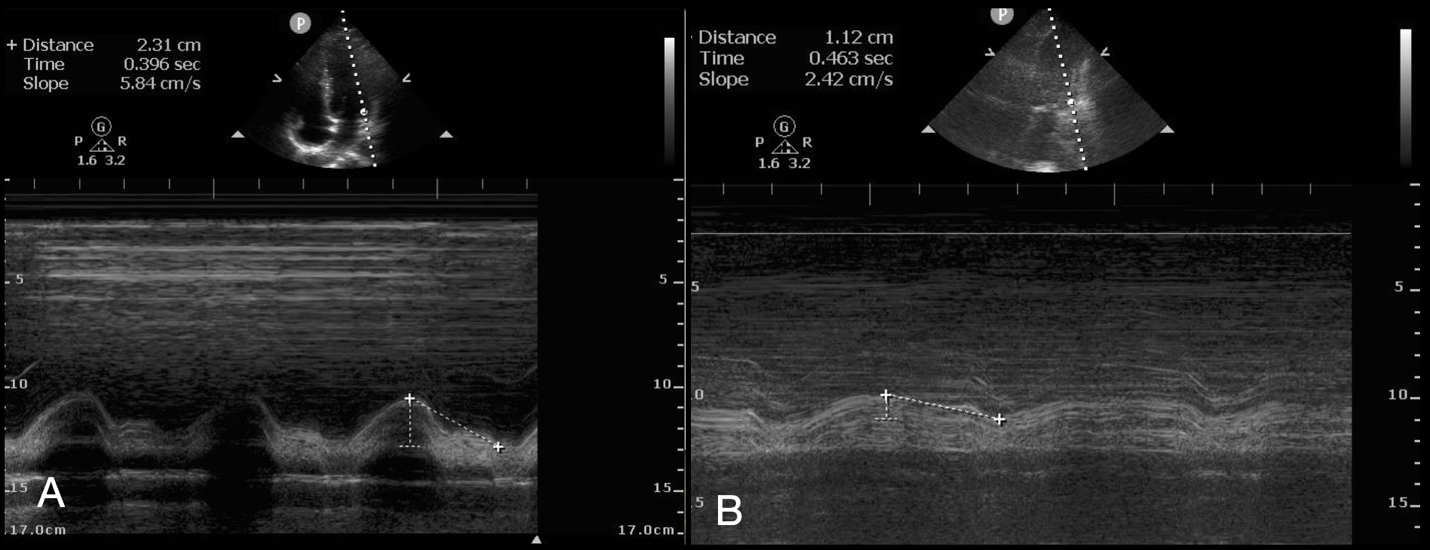

Mitral annular plane systolic excursion (MAPSE) has recently emerged as an adjunct to help assess LV function (22,23). MAPSE is performed by performing an M-mode evaluation of the lateral annulus of the mitral valve and measuring peak to trough of the resulting wave (Figure 1). A MAPSE < 8mm predicts an ejection fraction < 50%, whereas normal is between 12-15 mm. MAPSE can be beneficial when the E-point septal separation (EPSS) is inaccurate such as in mitral stenosis or LV hypertrophy and the operator desires confirmation beyond visual estimation of an abnormal LV function (24).

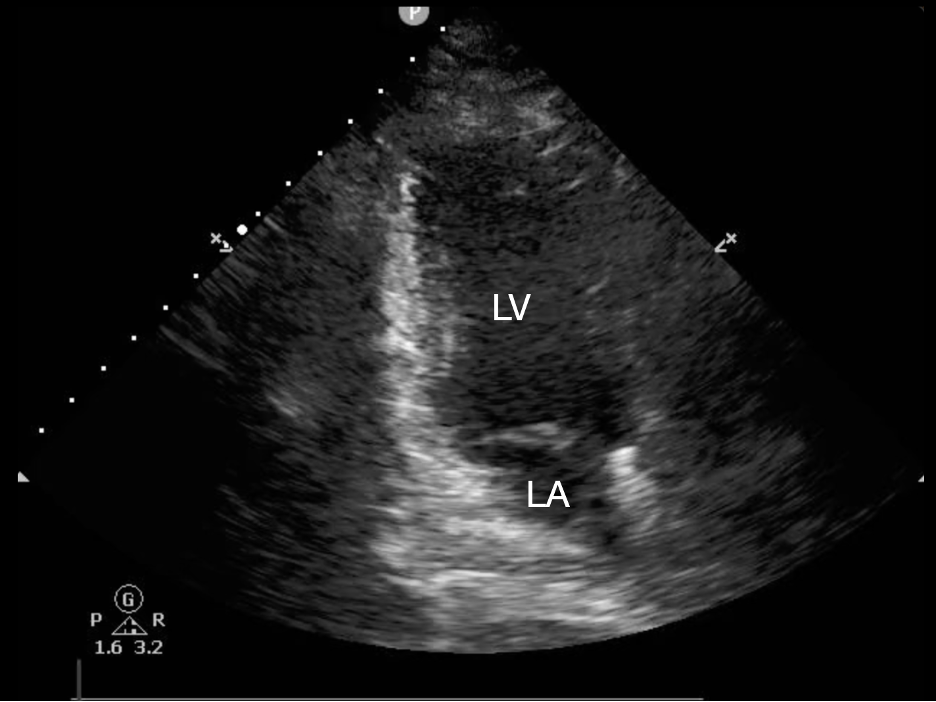

In addition to the visual estimation of qualitative LV ejection, ultrasound manufacturers have developed proprietary software which automatically calculates an ejection fraction using Simpson’s biplane method, similar to what cardiologists use in comprehensive echocardiograms (10,25). These applications can be found in both cart-based machines and handheld machines, and have been found in studies to be accurate in comparison to visual estimation by sonographers (26-28). These AI applications require an adequate apical four-chamber or apical two-chamber view to allow the software to identify and outline the LV wall in systole and diastole. The apical two-chamber view is obtained by first obtaining the apical four-chamber view and then rotating the indicator counterclockwise so that the RV is out of sight and the inferior and anterior walls of the LV are seen along with the left atrium (Figure 2). Operators using these tools can now more precisely quantify an EF, which can help both guide the admitting team and better assess changes from prior echocardiograms.

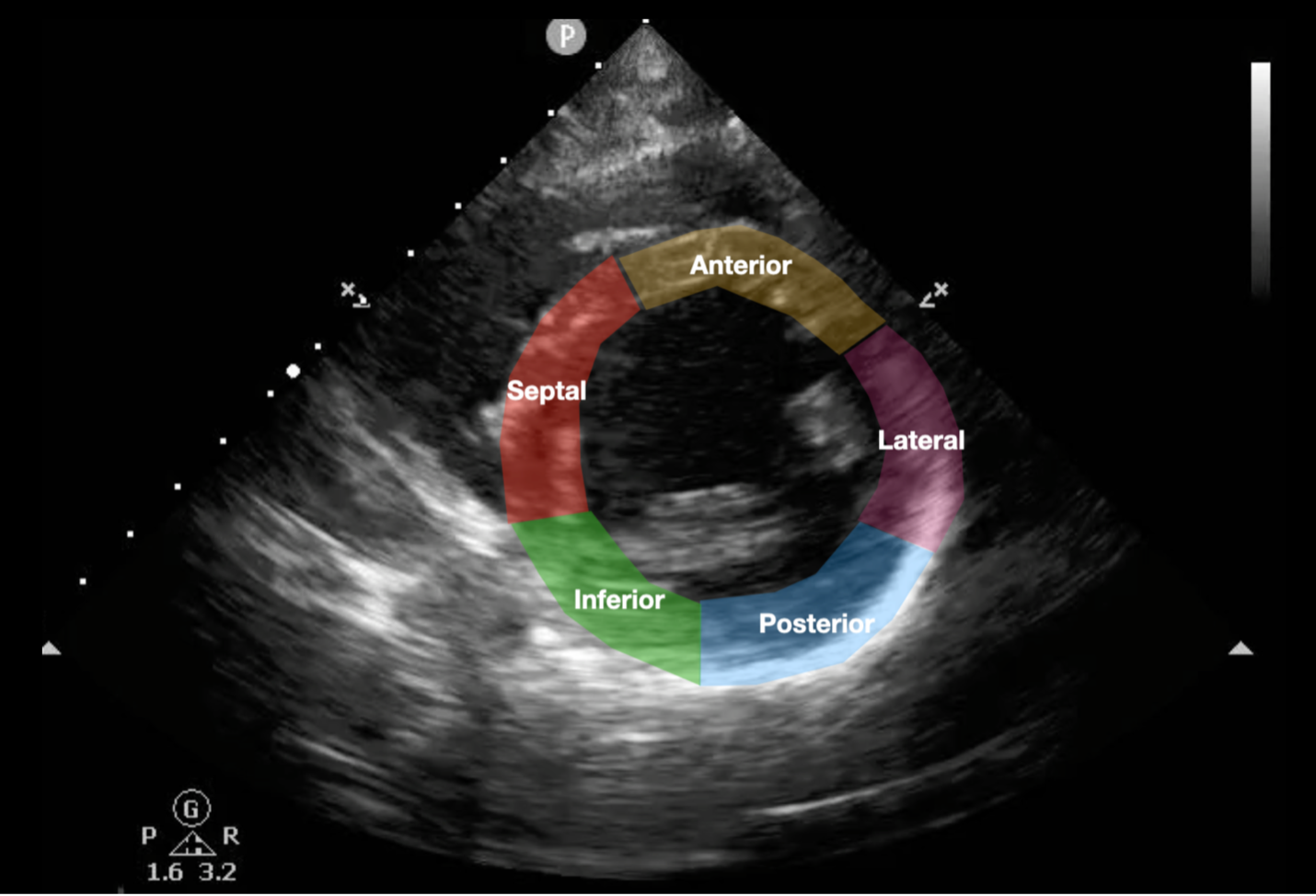

While ejection is meant to describe the overall global cardiac function, as skills with cardiac POCUS advance, operators can incorporate evaluation for focal wall motion abnormalities (FWMA). Assessing all walls circumferentially in the parasternal short axis (PSSA) using SALPI (septal, anterior, lateral, posterior, inferior walls) ensures that all myocardial walls are evaluated (Figure 3). In the setting of an occlusive myocardial infarction, even without ST segment elevation, a FWMA can suggest the need for cardiac catheterization early in the patient course, even before troponin results (29,30). The apical four-chamber and apical two-chamber views can also be used to assess for FWMA, and improve detection of apical FWMA (31). AI programs have also been shown to be accurate in detecting FWMA after training (32). Speckle tracking to look for myocardial strain has also been shown to be effective in identifying myocardial damage prior to ST elevations on the electrocardiogram, and the technology has been added to POCUS machines (33-35). There are limitations of speckle tracking including the need for software upgrades to ultrasound machines, the use of cardiac leads to ensure accurate identification of systole and diastole, and that it may not be sensitive enough to detect acute coronary syndrome accurately (34).

POCUS remains highly effective in detecting pericardial effusions and assessing for cardiac tamponade. Recent studies emphasize the importance of multiple images and clinical context for accurate diagnosis, particularly in challenging cases like pulmonary hypertension.

The assessment for FWMA can be improved either by placing a finger directly in the center of the screen to assess whether all walls equally collapse, or by blocking off other walls with a hand to limit the assessment to one wall at a time. A pitfall in assessing for FWMA in the PSSA only is that the assessment is limited to the mid-papillary view of the LV. Additionally, if the view is oblique, meaning the LV is elliptical instead of round, it can mimic a FWMA and lead to an incorrect interpretation. Finally, the presence of a FWMA does not indicate when the myocardial damage occurred, and patients with a past medical history of a myocardial infarction may have residual FWMA on POCUS. The finding of a FWMA should be contextualized with the patient’s electrocardiogram and presenting symptoms.

Ejection also includes the lack of myocardial activity in cardiac arrest. The use of POCUS in cardiac arrest has expanded in recent years, and getting a limited cardiac view within the 10 second pulse check is important to assess for a cause of cardiac arrest (36-38). There is, however, a significant discrepancy among ultrasound trained emergency physicians as to what defines cardiac standstill in both the adult and pediatric populations, and there has yet to be a consensus on the topic (39,40). Cardiac function is a continuum, and where to separate what constitutes significant or meaningful cardiac activity from agonal myocardial twitches can be difficult. In our experience, the lack of full valvular closure of the mitral or tricuspid valves typically indicates the lack of significant myocardial activity.

The lack of significant myocardial activity on POCUS is associated with poor patient outcomes and should be considered in the decision to cease resuscitation (41). The optimal view for visualizing cardiac activity in cardiac arrest has also come into question, as the subxiphoid view can be difficult to get in patients with a larger body habitus or with abdominal distension (38). An apical four-chamber view can visualize the heart without interfering with the compressions, and can be easier to obtain than the subxiphoid view. In the event other views are unable to be obtained, a parasternal long axis (PSLA) view can be utilized. However, care must be taken to remove any ultrasound gel from the anterior chest wall prior to compressions resuming. A recent study by Rolston et al. has shown no difference in success rate between the subxiphoid, apical four-chamber, or PSLA views when reviewing video of resuscitations (42).

POCUS can quickly evaluate left ventricular (LV) function, offering critical insights into conditions like heart failure. New tools, such as mitral annular plane systolic excursion (MAPSE) and AI-driven ejection fraction measurements, help refine diagnosis.

POCUS can also be used during cardiac arrest to guide the appropriate location of compressions. In particular, when using a device such as the Lund University Cardiopulmonary Assist System (LUCAS) cardiac POCUS can help guide appropriate device placement. Appropriate compressions should adequately compress the left ventricular rather than the inferior vena cava or aortic outflow tract (43,44).

Equality

Equality refers to the relative size of the RV to the LV. The ratio of the RV:LV is classically less than 0.6:1, with the ratio increasing as the RV dilates secondary to an increase in pulmonary arterial pressure (3). We have suggested using “equality,” or a 1:1 RV:LV ratio as the cutoff when assessing for RV dilation. Although this finding is specific, it has lower sensitivity (45,46). RV dilatation can be acute, chronic, or acute-on-chronic, and may be secondary to a multitude of pathologies besides pulmonary embolism (PE) such as long-standing pulmonary arterial hypertension, acute chest syndrome, cardiac arrest, RV ST-elevation myocardial infarction, or cor pulmonale (46).

The implementation of Pulmonary Embolism Response Teams (PERT) has emerged in the last decade with aims to improve, expedite, and standardize PE treatment, particularly in higher risk PE (47). The presence of right heart strain in a suspected or documented PE can be rapidly determined by the team at the bedside using cardiac POCUS. The presence of RV strain (with or without biomarkers) places the patient into an intermediate or higher risk zone which may be more appropriately treated with catheter directed therapies or systemic thrombolysis (48).

While the use of an RV:LV ratio cutoff of 1:1 or greater is more specific than sensitive, recent studies have shown that the combination of cardiac POCUS and abnormal vital signs can increase the sensitivity to over 95% for ruling out PE, making cardiac POCUS a useful tool to exclude significant PE in these patients. The presence of a normal tricuspid plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) in a patient with suspected PE and tachycardia can essentially exclude PE as a diagnosis (49). Other studies have shown improved diagnostic test characteristics by combining deep vein thrombosis (DVT) assessment with POCUS to increase sensitivity (50-52).

McConnell’s sign, the finding of hypokinesis or akinesis of the RV free wall with preserved apical motion, can also help determine right heart strain, and is thought to be associated with acute strain as opposed to chronic strain (53,54). This finding has previously been shown to be highly specific for PE, with some literature demonstrating a specificity approaching 100% (45,55). However, the high specificity of McConnell’s sign has been called into question recently. Case reports have demonstrated McConnell’s sign in patients with pulmonary hypertension from other underlying conditions, in cases of RV ischemia or infarction, or those with acute chest syndrome (56-59). Thus, McConnell’s sign does not exclude the presence of pathologies other than PE.

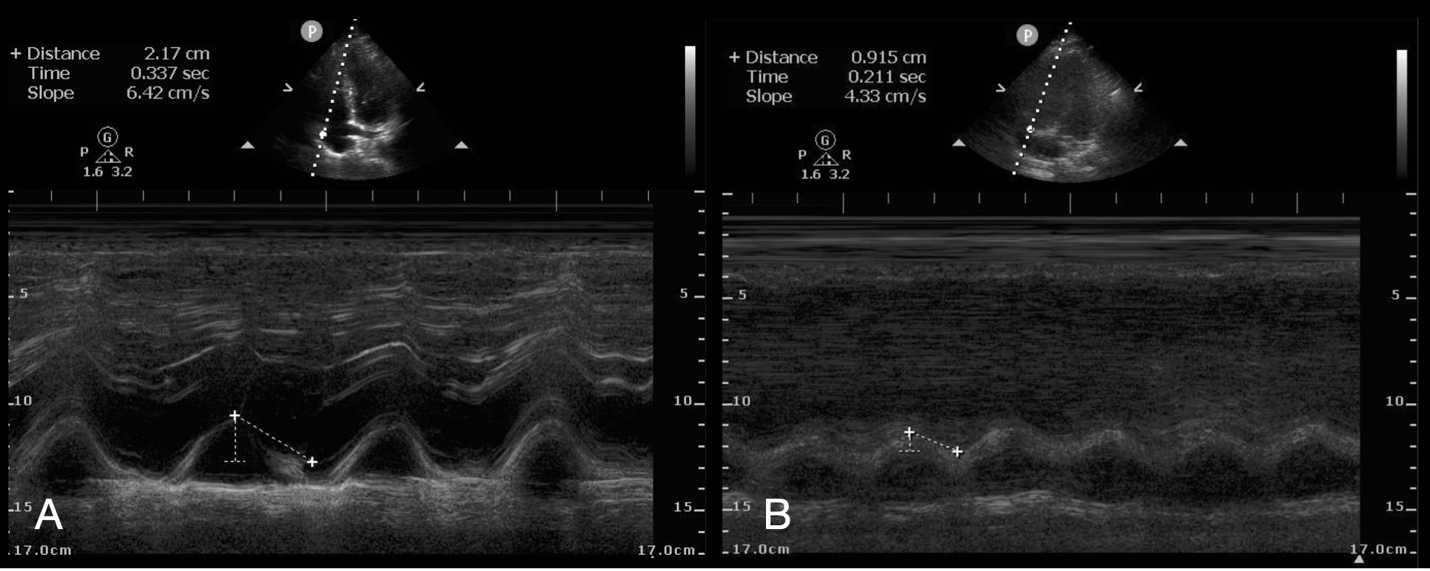

Given the limitations of using an abnormal RV:LV ratio as the sole diagnostic evaluation for PE, more recent POCUS literature evaluated the significance of other echocardiographic findings of acute RV dysfunction. TAPSE uses M-mode at the lateral tricuspid valve annulus to measure dynamic movement and generate a wave of movement that can be measured from peak to trough; the value of < 17 mm is considered abnormal (Figure 4). TAPSE can be performed with high interobserver reliability amongst emergency physicians (50,60,61). One pitfall of TAPSE is the need for good visualization of the lateral RV wall, which can be difficult in some patients. Improving patient positioning with the left arm raised above the head and a left lateral decubitus tilt can sometimes improve image quality.

Lastly, the 60/60 sign is another sonographic sign for PE that has had increasing interest in determining the presence of acute RV dysfunction. This is found by determining both the TR pressure gradient and the pulmonary acceleration time; a finding of ≤60 mmHg and ≤60 ms, respectively, in a patient being evaluated for PE has high specificity though low sensitivity (60,62). The 60/60 sign requires the presence of TR and the use of color Doppler and pulsed wave Doppler, making it a more advanced calculation, but can help to differentiate between acute and chronic RV strain (60,62).

Exit

Measuring the aortic outflow tract (AOFT) diameter, or “exit,” is an essential component of cardiac POCUS and is effectively visualized in the PSLA, providing an excellent depiction for accurate measurement and diagnosis of ascending aortic aneurysm. Although visualizing an intimal flap could directly indicate aortic dissection, AOFT dilation has been associated with a high risk of major adverse aortic events, such as dissection (63). The initial approach of the 5 Es recommended measuring from the leading edge to the leading edge, spanning from the outer wall to the inner wall (OTI) in the PSLA view (3). Notably, this proposed approach demonstrated a strong correlation with inner-edge to inner-edge measurements obtained from CT, further supporting its accuracy and clinical relevance in suspected patients (64). Although a normal AOFT diameter cannot rule out aortic dissection, nor can its dilation confirm the diagnosis, the significance of cardiac POCUS in improving the time to diagnosis is noteworthy, given a reduction of 146 minutes in patients with aortic dissection who received cardiac POCUS as an initial diagnostic test (65). In particular, the presence of a dilated AOFT in combination with a pericardial effusion is highly suggestive of a type A dissection.

The upper limit of normal for the AOFT has been subject to additional research. The diameter of ≥ 4 cm in PSLA view with the OTI method showed a sensitivity and specificity ranging from 59.6% to 78.6% and 85.4% to 92.9%, respectively, for acute aortic syndromes (66,67). A more recent study by Gibbons et al. utilized a lower cutoff of 3.5 cm and yielded a sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 91.8% for the diagnosis of aortic dissection (68). While this study had a strong sensitivity and specificity, the positive predictive value (PPV) for this method was notably low (16.8%) given the amount of patients without an aortic dissection who ruled into the study based on the AOFT measurement alone. Notably, this study utilized an inner-to-inner (ITI) method of measurement, so a higher cutoff would be needed for the more widely accepted OTI measurement technique (69,70). We continue to recommend the use of the OTI measurement, with < 4 cm as normal, 4.0 – 4.5 cm as borderline, and ≥ 4.5 cm as dilated for the AOFT measurement as discussed in the original article (3).

With the rise in AI and machine learning algorithms in POCUS, the AOFT measurement may be automated in the future, although no current real-time measurement tool is commercially available at this time.

Entrance

The IVC is best visualized by finding the subxiphoid cardiac view and then rotating the probe indicator towards the patient’s head, rocking inferiorly to center the liver in the screen, and then sliding to the patient’s right (3). The main use of the IVC in POCUS is to assess for volume status, with measurement of the IVC at end expiration ≥ 2 cm considered plethoric (volume overload), and < 1 cm considered flat (volume depletion). This measurement can be performed by freezing the image or using M-mode over a respiratory cycle. This measurement’s usefulness is highlighted by its ability to noninvasively estimate right atrial pressure (RAP). A plethoric IVC > 2 cm suggests a pathologic RAP > 8 mmHg, whereas a plethoric IVC with less than 50% collapse suggests a RAP > 15 mmHg (71).

IVC assessment is also important in assessing right ventricular systolic pressure (RVSP). RVSP can be calculated if the patient has TR on color flow Doppler (CFD). In the presence of TR, continuous wave (CW) spectral Doppler can estimate the RV pressure gradient using peak TR velocity (V), which is then added to right atrial pressure (RAP) using the formula RVSP = 4V2 + RAP. RVSP can be elevated acutely in PE, or chronically in pulmonary hypertension (72).

In recent years, the accuracy of IVC measurement has been called into question and can be limited by clinical scenarios such as the cylinder tangent effect of being off-axis of the IVC, a chronically dilated IVC, pediatric limitations, TR, RV failure, COPD exacerbations, pregnancy, obstructive shock, mechanical ventilation, etc (73). To avoid some of these limitations, there has been increasing research into the other surrogates for measuring volume status such as the Venous Excess Ultrasound (VExUS). VExUS is applicable when the IVC is ≥ 2 cm, and uses both hepatic vein Doppler, portal vein Doppler, and renal vein Doppler to determine whether the patient is volume overloaded (74-76). VExUS, or portions of the VExUS assessment, are being investigated as more accurate ways to assess volume status.

The assessment of right ventricle (RV) dilation via the RV:LV ratio helps identify conditions like pulmonary embolism (PE) and right heart strain. Advances in POCUS, such as TAPSE and the 60/60 sign, enhance diagnostic accuracy for right heart dysfunction.

Tools have been developed to automatically measure the IVC and its collapsibility using AI (7,77). This tool is mostly useful for the novice operator, as previous studies have shown that experienced operators have moderate to good interrater reliability for visual estimation of IVC measurement and collapse (78).

Discussion and Future Directions

Cardiac POCUS can be incredibly useful in the evaluation of the acute patient presenting with chest pain, dyspnea, hypotension, or syncope. However, it can also be challenging to distill what information is needed and important. The 5 Es are an attempt to distill down the potential findings into a manageable protocol that will identify the most important emergent findings. We specifically excluded detailed valvular assessment as it is typically beyond the scope of POCUS, though this does not mean that POCUS could not identify significant or obvious valvular pathology.

In this review we have highlighted some techniques related to the 5 Es including use of m-mode and Doppler that may be more advanced than some users are comfortable with. Our intent is to review and reinforce the 5 Es while providing some additional techniques and considerations for those who are comfortable with basic cardiac POCUS evaluation, and to bring up other possibilities for augmenting evaluation. These techniques are not always necessary, and each sonographer should use approaches that they are comfortable with.

The advent of AI is exciting and touched on in this paper. A future can be imagined where relatively novice users are guided through image acquisition and interpretation with good accuracy. However, we are far from the point where AI will replace an experienced sonographer. The effective use of cardiac POCUS requires knowing when to use it, how to acquire good images, interpretation of these images, and incorporation of findings into diagnosis and clinical care. The full scope of doing this in an automated manner is not something that is on the immediate horizon.

The acquisition of cardiac images can be challenging and there are some AI solutions in this space. In 2020, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first system to help guide a user in image acquisition for cardiac POCUS (79). There are an increasing number of publications that purport to demonstrate reliability and accuracy of interpretation. However, many of these algorithms remain proprietary and are not available for evaluation and general use. Ultrasound manufacturers are rapidly trying to develop and deploy AI, however, this requires the purchase of equipment or software with this capability, and each of these algorithms may be slightly different.

In the United States, the FDA regulates the use of devices for medical diagnosis. While the quantification of certain parameters (for example EF or IVC diameter) is more straightforward and these devices are in use, the threshold for approval of an actual diagnosis (such as “tamponade”) is a much higher bar.

Perhaps one of the more immediate applications for AI will be in education and quality assurance. It is quite feasible in the near future that AI will be able to “flag” examinations for review where the interpretation rendered by a less experienced user is discrepant from the AI interpretation. This can streamline review by more experienced sonographers to provide valuable feedback. AI could also be helpful in identifying cases on a large scale for research purposes.

The potential for more “open-source” or “open-access” AI has yet to be realized. While commercially available solutions are increasing, they come with cost and the need to evaluate and use each solution separately with proprietary equipment. Many academic institutions are developing AI solutions that would benefit from more widespread dissemination that allow testing and applications on local data. We look forward to a future when there is freely available and generally applicable AI solutions in this space. It is possible that a Chat-GPT like model for medical imaging may be developed at some point.

Conclusion

Cardiac POCUS remains an essential tool in the evaluation of the acutely ill patient, and the 5 Es provide a framework for identifying important pathology. In this review we hope to emphasize the 5 Es and highlight refinements and additional methods for evaluation, but the underlying physiology and pathology remain the same. Artificial intelligence is developing rapidly, but the need for sonographers who can effectively obtain, interpret, and integrate cardiac POCUS into the care of their patients is still paramount.

References

- Smalley CM, Simon EL, Muir MR, Fertel BS. A Real-World Experience: Retrospective Review of Point-of-Care Ultrasound Utilization and Quality in Community Emergency Departments. West J Emerg Med. 2023;24(4):685-92. doi:10.5811/westjem.58965

- Moore CL, Copel JA. Point-of-Care Ultrasonography. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(8):749-757. doi:10.1056/NEJMra0909487

- Kennedy Hall M, Coffey EC, Herbst M, et al. The “5Es” of emergency physician-performed focused cardiac ultrasound: a protocol for rapid identification of effusion, ejection, equality, exit, and entrance. Acad Emerg Med. May 2015;22(5):583-93. doi:10.1111/acem.12652

- Boivin Z, Carpenter S, Lee G, et al. Evaluation of a Required Vertical Point-of-Care Ultrasound Curriculum for Undergraduate Medical Students. Cureus. 2022;14(10):e30002. doi:10.7759/cureus.30002

- Bahner DP, Goldman E, Way D, Royall NA, Liu YT. The state of ultrasound education in U.S. medical schools: results of a national survey. Academic medicine: journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2014;89(12):1681-6. doi:10.1097/acm.0000000000000414

- Gottlieb M, Cooney R, King A, et al. Trends in point-of-care ultrasound use among emergency medicine residency programs over a 10-year period. AEM Educ Train. 2023;7(2):e10853. doi:10.1002/aet2.10853

- Gohar E, Herling A, Mazuz M, et al. Artificial Intelligence (AI) versus POCUS Expert: A Validation Study of Three Automatic AI-Based, Real-Time, Hemodynamic Echocardiographic Assessment Tools. J Clin Med. 2023;12(4) doi:10.3390/jcm12041352

- Zhai S, Wang H, Sun L, et al. Artificial intelligence (AI) versus expert: A comparison of left ventricular outflow tract velocity time integral (LVOT-VTI) assessment between ICU doctors and an AI tool. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2022;23(8):e13724. doi:10.1002/acm2.13724

- Cheema BS, Walter J, Narang A, Thomas JD. Artificial Intelligence-Enabled POCUS in the COVID-19 ICU: A New Spin on Cardiac Ultrasound. JACC. 2021:258-263. vol. 2.

- Gottlieb M, Schraft E, O’Brien J, Patel D. Diagnostic accuracy of artificial intelligence for identifying systolic and diastolic cardiac dysfunction in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med. 2024;86:115-119. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2024.10.019

- Hoit BD. Pericardial Effusion and Cardiac Tamponade in the New Millennium. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2017;19(7):57. doi:10.1007/s11886-017-0867-5

- Alerhand S, Adrian RJ, Long B, Avila J. Pericardial tamponade: A comprehensive emergency medicine and echocardiography review. Am J Emerg Med. 2022;58:159-174. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2022.05.001

- Hoch VC, Abdel-Hamid M, Liu J, Hall AE, Theyyunni N, Fung CM. ED point-of-care ultrasonography is associated with earlier drainage of pericardial effusion: A retrospective cohort study. Am J Emerg Med. 2022;60:156-163. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2022.08.008

- Schaeffer WJ, Elegante M, Fung CM, Huang R, Theyyunni N, Tucker R. Variability in Interpretation of Echocardiographic Signs of Tamponade: A Survey of Emergency Physician Sonographers. J Emerg Med. 2024;66(3):e346-e353. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2023.10.021

- Adrian RJ, Alerhand S, Liteplo A, Shokoohi H. Is pulmonary hypertension protective against cardiac tamponade? A systematic review. Internal and emergency medicine. 2024;19(7):1987-2003. doi:10.1007/s11739-024-03566-y

- Cheng CY, Wu CC, Chen HC, et al. Development and validation of a deep learning pipeline to measure pericardial effusion in echocardiography. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2023;10:1195235. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2023.1195235

- Jevsikov J, Ng T, Lane ES, et al. Automated mitral inflow Doppler peak velocity measurement using deep learning. Comput Biol Med. 2024/03/01/ 2024;171:108192. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2024.108192

- Chiu IM, Vukadinovic M, Sahashi Y, et al. Automated Evaluation for Pericardial Effusion and Cardiac Tamponade with Echocardiographic Artificial Intelligence. medRxiv. 2024. doi:10.1101/2024.11.27.24318110

- Randazzo MR, Snoey ER, Levitt MA, Binder K. Accuracy of emergency physician assessment of left ventricular ejection fraction and central venous pressure using echocardiography. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10(9):973-7. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2003.tb00654.x

- Unlüer EE, Karagöz A, Akoğlu H, Bayata S. Visual estimation of bedside echocardiographic ejection fraction by emergency physicians. West J Emerg Med. 2014;15(2):221-6. doi:10.5811/westjem.2013.9.16185

- Moore CL, Rose GA, Tayal VS, Sullivan DM, Arrowood JA, Kline JA. Determination of left ventricular function by emergency physician echocardiography of hypotensive patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9(3):186-93. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2002.tb00242.x

- Schick AL, Kaine JC, Al-Sadhan NA, et al. Focused cardiac ultrasound with mitral annular plane systolic excursion (MAPSE) detection of left ventricular dysfunction. Am J Emerg Med. 2023;68:52-8. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2023.03.018

- Cirin L, Crișan S, Luca CT, et al. Mitral Annular Plane Systolic Excursion (MAPSE): A Review of a Simple and Forgotten Parameter for Assessing Left Ventricle Function. J Clin Med. 2024;13(17.). doi:10.3390/jcm13175265

- Núñez-Ramos JA, Pana-Toloza MC, Palacio-Held SC. E-Point Septal Separation Accuracy for the Diagnosis of Mild and Severe Reduced Ejection Fraction in Emergency Department Patients. Pocus J. 2022;7(1):160-165. doi:10.24908/pocus.v7i1.15220

- Aronovitz N, Hazan I, Jedwab R, et al. The effect of real-time EF automatic tool on cardiac ultrasound performance among medical students. PLoS One. 2024;19(3):e0299461. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0299461

- Vega R, Kwok C, Rakkunedeth Hareendranathan A, Nagdev A, Jaremko JL. Assessment of an Artificial Intelligence Tool for Estimating Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction in Echocardiograms from Apical and Parasternal Long-Axis Views. Diagnostics (Basel). 2024;14(16). doi:10.3390/diagnostics14161719

- Abazid RM, Abohamr SI, Smettei OA, et al. Visual versus fully automated assessment of left ventricular ejection fraction. Avicenna J Med. 2018;8(2):41-45. doi:10.4103/ajm.AJM_209_17

- He B, Kwan AC, Cho JH, et al. Blinded, randomized trial of sonographer versus AI cardiac function assessment. Nature. 2023;616(7957):520-4. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-05947-3

- Xu C, Melendez A, Nguyen T, et al. Point-of-care ultrasound may expedite diagnosis and revascularization of occult occlusive myocardial infarction. Am J Emerg Med. 2022;58:186-191. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2022.06.010

- Xu Tan T, Wright D, Baloescu C, Lee S, Moore CL. Emergency Physician-performed Echocardiogram in Non-ST Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome Patients Requiring Coronary Intervention. West J Emerg Med. 2024;25(1):9-16. doi:10.5811/westjem.60508

- Lebeau R, Robert-Halabi M, Pichette M, et al. Left ventricular ejection fraction using a simplified wall motion score based on mid-parasternal short axis and apical four-chamber views for non-cardiologists. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2023;23(1):115. doi:10.1186/s12872-023-03141-x

- Slivnick JA, Gessert NT, Cotella JI, et al. Echocardiographic Detection of Regional Wall Motion Abnormalities Using Artificial Intelligence Compared to Human Readers. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2024;37(7):655-663. doi:10.1016/j.echo.2024.03.017

- Rowland-Fisher A, Smith S, Laudenbach A, Reardon R. Diagnosis of acute coronary occlusion in patients with non-STEMI by point-of-care echocardiography with speckle tracking. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(9):1914.e3-6. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2016.02.017

- Reardon L, Scheels WJ, Singer AJ, Reardon RF. Feasibility and accuracy of speckle tracking echocardiography in emergency department patients. Am J Emerg Med. 2018;36(12):2254-2259. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2018.08.074

- Mondillo S, Galderisi M, Mele D, et al. Speckle-tracking echocardiography: a new technique for assessing myocardial function. J Ultrasound Med. 2011;30(1):71-83. doi:10.7863/jum.2011.30.1.71

- Magon F, Longhitano Y, Savioli G, et al. Point-of-Care Ultrasound (POCUS) in Adult Cardiac Arrest: Clinical Review. Diagnostics (Basel). 2024;14(4). doi:10.3390/diagnostics14040434

- Zaki HA, Iftikhar H, Shaban EE, et al. The role of point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) imaging in clinical outcomes during cardiac arrest: a systematic review. The ultrasound journal. 2024;16(1):4. doi:10.1186/s13089-023-00346-1

- Gottlieb M, Alerhand S. Managing Cardiac Arrest Using Ultrasound. Ann Emerg Med. 2023;81(5):532-542. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2022.09.016

- Yanni E, Tsung JW, Hu K, Tay ET. Interpretation of Cardiac Standstill in Children Using Point-of-Care Ultrasound. Ann Emerg Med. 2023;82(5):566-572. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2023.04.003

- Hu K, Gupta N, Teran F, Saul T, Nelson BP, Andrus P. Variability in Interpretation of Cardiac Standstill Among Physician Sonographers. Ann Emerg Med. 2018;71(2):193-198. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2017.07.476

- Lalande E, Burwash-Brennan T, Burns K, et al. Is point-of-care ultrasound a reliable predictor of outcome during traumatic cardiac arrest? A systematic review and meta-analysis from the SHoC investigators. Resuscitation. 2021;167:128-136. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.08.027

- Rolston DM, Haddad G, Sales N, et al. Success of focused transthoracic echocardiography locations for cardiac visualization during cardiac arrest: A video-review analysis. Resusc Plus. 2024;20:100774. doi:10.1016/j.resplu.2024.100774

- Liu RB, Bogucki S, Marcolini EG, et al. Guiding Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation with Focused Echocardiography: A Report of Five Cases. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2020;24(2):297-302. doi:10.1080/10903127.2019.1626955

- Boivin Z, Hossin T, Colucci L, Moore CL, Liu R. Man in cardiac arrest. Ann Emerg Med. 2024;84(2):213-214. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2024.02.019

- Dresden S, Mitchell P, Rahimi L, et al. Right ventricular dilatation on bedside echocardiography performed by emergency physicians aids in the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;63(1):16-24. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2013.08.016

- Taylor RA, Moore CL. Accuracy of emergency physician-performed limited echocardiography for right ventricular strain. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2014;32(4):371-374. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2013.12.043

- Rivera-Lebron B, McDaniel M, Ahrar K, et al. Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow Up of Acute Pulmonary Embolism: Consensus Practice from the PERT Consortium. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2019;25:1076029619853037. doi:10.1177/1076029619853037

- Moore C, McNamara K, Liu R. Challenges and Changes to the Management of Pulmonary Embolism in the Emergency Department. Clin Chest Med. 2018;39(3):539-547. doi:10.1016/j.ccm.2018.04.009

- Daley J, Grotberg J, Pare J, et al. Emergency physician performed tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion in the evaluation of suspected pulmonary embolism. Am J Emerg Med. 2017;35(1):106-111. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2016.10.018

- Daley JI, Dwyer KH, Grunwald Z, et al. Increased Sensitivity of Focused Cardiac Ultrasound for Pulmonary Embolism in Emergency Department Patients With Abnormal Vital Signs. Acad Emerg Med. 2019;26(11):1211-1220. doi:10.1111/acem.13774

- Dwyer KH, Rempell JS, Stone MB. Diagnosing centrally located pulmonary embolisms in the emergency department using point-of-care ultrasound. Am J Emerg Med. 2018;36(7):1145-1150. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2017.11.033

- Falster C, Mørkenborg MD, Thrane M, et al. Utility of ultrasound in the diagnostic work-up of suspected pulmonary embolism: an open-label multicentre randomized controlled trial (the PRIME study). Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2024;42:100941. doi:10.1016/j.lanepe.2024.100941

- McConnell MV, Solomon SD, Rayan ME, Come PC, Goldhaber SZ, Lee RT. Regional right ventricular dysfunction detected by echocardiography in acute pulmonary embolism. The American journal of cardiology. 1996;78(4):469-73. doi:10.1016/s0002-9149(96)00339-6

- Brenes-Salazar JA. McConnell’s echocardiographic sign in acute pulmonary embolism: still a useful pearl. Heart Lung Vessel. 2015;7(1):86-88.

- Fields JM, Davis J, Girson L, et al. Transthoracic Echocardiography for Diagnosing Pulmonary Embolism: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2017;30(7):714-723.e4. doi:10.1016/j.echo.2017.03.004

- Walsh BM, Moore CL. McConnell’s Sign Is Not Specific for Pulmonary Embolism: Case Report and Review of the Literature. J Emerg Med. 2015;49(3):301-304. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2014.12.089

- Rafie N, Foley David A, Ripoll Juan G, et al. McConnell’s Sign Is Not Always Pulmonary Embolism. JACC: Case Reports. 2022;4(13):802-807. doi:10.1016/j.jaccas.2022.05.007

- McCutcheon JB, Schaffer P, Lyon M, Gordon R. The McConnell Sign is Seen in Patients With Acute Chest Syndrome. J Ultrasound Med. 2018;37(10):2433-2437. doi:10.1002/jum.14585

- Vaid U, Singer E, Marhefka GD, Kraft WK, Baram M. Poor positive predictive value of McConnell’s sign on transthoracic echocardiography for the diagnosis of acute pulmonary embolism. Hospital practice 2013;41(3):23-7. doi:10.3810/hp.2013.08.1065

- Alerhand S, Sundaram T, Gottlieb M. What are the echocardiographic findings of acute right ventricular strain that suggest pulmonary embolism? Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2021;40(2):100852. doi:10.1016/j.accpm.2021.100852

- Alerhand S, Hickey SM. Tricuspid Annular Plane Systolic Excursion (TAPSE) for Risk Stratification and Prognostication of Patients with Pulmonary Embolism. J Emerg Med. 2020;58(3):449-456. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2019.09.017

- Shah BR, Velamakanni SM, Patel A, Khadkikar G, Patel TM, Shah SC. Analysis of the 60/60 Sign and Other Right Ventricular Parameters by 2D Transthoracic Echocardiography as Adjuncts to Diagnosis of Acute Pulmonary Embolism. Cureus. 2021;13(3):e13800. doi:10.7759/cureus.13800

- Kalogerakos PD, Zafar MA, Li Y, et al. Root Dilatation Is More Malignant Than Ascending Aortic Dilation. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10(14):e020645. doi:10.1161/jaha.120.020645

- Hiratzka LF, Bakris GL, Beckman JA, et al. ACCF/AHA/AATS/ACR/ASA/SCA/SCAI/SIR/STS/SVM guidelines for the diagnosis and management of patients with Thoracic Aortic Disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American College of Radiology, American Stroke Association, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Interventional Radiology, Society of Thoracic Surgeons, and Society for Vascular Medicine. Circulation. 2010;121(13):e266-369. doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181d4739e

- Pare JR, Liu R, Moore CL, et al. Emergency physician focused cardiac ultrasound improves diagnosis of ascending aortic dissection. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(3):486-92. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2015.12.005

- Nazerian P, Vanni S, Morello F, et al. Diagnostic performance of focused cardiac ultrasound performed by emergency physicians for the assessment of ascending aorta dilation and aneurysm. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22(5):536-41. doi:10.1111/acem.12650

- Nazerian P, Mueller C, Vanni S, et al. Integration of transthoracic focused cardiac ultrasound in the diagnostic algorithm for suspected acute aortic syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2019;40(24):1952-1960. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehz207

- Gibbons RC, Smith D, Feig R, Mulflur M, Costantino TG. The sonographic protocol for the emergent evaluation of aortic dissections (SPEED protocol): A multicenter, prospective, observational study. Acad Emerg Med. 2024;31(2):112-118. doi:10.1111/acem.14839

- Rodríguez-Palomares JF, Teixidó-Tura G, Galuppo V, et al. Multimodality Assessment of Ascending Aortic Diameters: Comparison of Different Measurement Methods. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2016;29(9):819-826.e4. doi:10.1016/j.echo.2016.04.006

- Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015;28(1):1-39.e14. doi:10.1016/j.echo.2014.10.003

- De Vecchis R, Baldi C, Giandomenico G, Di Maio M, Giasi A, Cioppa C. Estimating Right Atrial Pressure Using Ultrasounds: An Old Issue Revisited With New Methods. J Clin Med Res. 2016;8(8):569-74. doi:10.14740/jocmr2617w

- Avriel A, Bar Lavie Shay A, Hershko Klement A, et al. Point-of-Care Ultrasonography in a Pulmonary Hypertension Clinic: A Randomized Pilot Study. J Clin Med. 2023;12(5). doi:10.3390/jcm12051752

- Di Nicolò P, Tavazzi G, Nannoni L, Corradi F. Inferior Vena Cava Ultrasonography for Volume Status Evaluation: An Intriguing Promise Never Fulfilled. J Clin Med.2023;12(6). doi:10.3390/jcm12062217

- Rihl MF, Pellegrini JAS, Boniatti MM. VExUS Score in the Management of Patients With Acute Kidney Injury in the Intensive Care Unit: AKIVEX Study. J Ultrasound Med. 2023;42(11):2547-2556. doi:10.1002/jum.16288

- Beaubien-Souligny W, Rola P, Haycock K, et al. Quantifying systemic congestion with Point-Of-Care ultrasound: development of the venous excess ultrasound grading system. The ultrasound journal. 2020;12(1):16. doi:10.1186/s13089-020-00163-w

- Assavapokee T, Rola P, Assavapokee N, Koratala A. Decoding VExUS: a practical guide for excelling in point-of-care ultrasound assessment of venous congestion. The ultrasound journal. 2024;16(1):48. doi:10.1186/s13089-024-00396-z

- Blaivas M, Adhikari S, Savitsky EA, Blaivas LN, Liu YT. Artificial intelligence versus expert: a comparison of rapid visual inferior vena cava collapsibility assessment between POCUS experts and a deep learning algorithm. Journal of the American College of Emergency Physicians open. 2020;1(5):857-864. doi:10.1002/emp2.12206

- Fields JM, Lee PA, Jenq KY, Mark DG, Panebianco NL, Dean AJ. The interrater reliability of inferior vena cava ultrasound by bedside clinician sonographers in emergency department patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18(1):98-101. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00952.x

- Administration FD. FDA Authorizes Marketing of First Cardiac Ultrasound Software That Uses Artificial Intelligence to Guide User. US FDA. Accessed 17 December, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-authorizes-marketing-first-cardiac-ultrasound-software-uses-artificial-intelligence-guide-user

Figure 1: Normal (A) and Abnormal (B) Mitral Annular Plane Systolic Excursion in the Apical 4-Chamber View

Figure 2: Apical 2-Chamber View with the Left Ventricle (LV) and Left Atrium (LA) Visualized. In this view the inferior wall is seen to the left of the image, while the anterior wall is to the right. This image is obtained by rotating the probe counterclockwise from the apical 4-chamber view. This image shows an emergency medicine orientation (indicator to screen left), so the indicator should be directed inferiorly. Should a cardiology orientation be used (indicator to screen right) the indicator should be directed superiorly after rotation.

Figure 3: Parasternal Short Axis View with Left Ventricular Wall Names (SALPI)

Figure 4: Normal (A) and Abnormal (B) Tricuspid Annular Plane Systolic Excursion in the Apical 4-Chamber View

Published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License